Silent whispers. The life of Petronilla Paolini Massimi

Some people live outside of normal time parameters, their voices are heard through their own seemingly modern words, and it’s easy to forget that they don’t belong to our time but were born in another historic reality.

Petronilla is one of these people, separated from us by three centuries yet we read, with emotion and involvement, about the events of her life, captured by the retelling in her own voice. Three centuries ago, yet we find a feminist consciousness, the idea of a woman’s autonomous role and awareness of her own abilities. It is she who wishes to speak to us about how she became who she was, not letting herself be transported by events but opposing them with tenacity and pride, “adverse to a fate” that would cheerfully drown her. It is she who bears witness, with the vigour and incisiveness of a modern writer, in that First Song (Primo Canzone), to the deeds of a‘special friend’ who luckily managed to escape the shipwreck of the poet’s pages through death. In these pages we find out about her unhappy love, her escape to a convent, the loss of her sons, and her redemption through poetry. However, her early days had been bright, she had had a loving family, high social status, the comforts of being well off, and a precocious intelligence.

Petronilla is remembered as the “poetess of Rome”, but she was actually born in Tagliacozzo, on 24 December 1663, Christmas Eve, under the cold stars of Capricorn, as in a fairy story. Just like in a fairytale, she lived, from birth, in castles, firstly at Magliano dei Marsi, then in Ortona, and her parents were from the nobility. Her father, Francesco Paolini, Baron of Ortona dei Marsi and Gentleman of the Colonna, was a highly cultured and successful politician. A brilliant, dynamic businessman, always on the move. Her mother, Silvia Argoli, was a native of Tagliacozzo, a thoughtful, introvert and lover of solitude. Here, in the countryside of Marsica, Petronilla lived her first and probably most carefree years, beneath the shadows of the rotund Mount Arunzo and the more severe and sharp Mount Bove, on the banks of the river Imele. It is here, many years later, where she returns on an emotional pilgrimage with her sons.

Tagliacozzo

Then something happens that unsettles her life, the death of her father, in an ambush that was perhaps organised by relatives of her mother. Petronilla tells us about it in one of her later compositions – “Tu sai che i lumi appena Apersi al dì, io m’incontrai dolente Coll’aspetto crudel d’avversa sorte, E con adulta pena In pargoletta età vidi Repente fin sulla cuna mia scherzar la Morte.”

In an instant her life changes, from the previous peace and calm into calamity. Petronilla is just four years old, she already loves poetry and singing and she is also quite wealthy, which has not gone unnoticed by certain relatives. We are told that they even tried to poison her. She still had her mother, sensitive like her, but unlike her daughter rather weak and resigned to her fate. Following the death of her husband her solitarynature takes over and she wishes only to enclose herself in a convent. In 1667 the little Petronilla is sent to Rome, far from her envious relatives, to study at the Monastery of the Holy Ghost, better known as St Egidio’s, near the Traiano forum. For Petronilla this is an exile and the start of a new and different life, a long way from the mountain dressed countryside of her hometown.

A lively, Baroque Rome awaits her, inhabited by the likes of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Pietro da Cortona and Princess Cristina of Sweden. Petronilla is a lively, extrovert young girl who loves life and her studies. The big city doesn’t manage to subdue her, or her beauty and intelligence, and neither does her rich dowry go unnoticed here amongst the “greedy desires” of the Roman nobility. Petronilla remembers with fondness the silent halls where she studied, her love of the works of Tasso that she learnt by heart and her first pieces of poetry, that years later as an adult she would reread with emotion.

However, a few hundred kilometres is not distance enough to protect Petronilla from envy and greed. The until then protection she had been afforded by the Pontiff Clemente X, who had been kind to her, turned to condemnation, and in 1673 the Pope asked her mother to give her hand in marriage to one of his collaborators and cousins, Francesco Massimi di Aracoeli, Marquis of Ortona and Carreto, Vice Warden of Castel Sant’Angelo, and Papal General, almost thirty years Petronilla’s senior. Her mother, from within the walls of the convent, bound to her spiritual life, and plagued by fatalism, gave her consent. Again in her First Song, with words laden with horror, Petronilla talks about that April in her life, co-joined to the “strange senile era” of Prince Francesco Massimi. The Pope aided the situation in favour of his cousin with an ob defectum aetatis dispensation for the future wife, making the marriage legitimate despite her young age. The marriage was celebrated in the chapel of the monastery on 8th November 1673.

The still only 10 year old Petronilla remained with her mother at the monastery for a while, until she moved, in 1675 to Massimi’s Palace in Ara Coeli, where she stayed under the protective gaze of an old sister-in-law of Francesco. Finally in 1678 she joined her husband at Castel Sant’ Angelo, which at that time was being used as a prison, and home to the Papal Guards. So began the second traumatic episode in the life of Petronilla, and the start of her third age. After the initial period of juvenile curiosity and enthusiasm for marriage to an important and brave person, cousin of the pope even, disappointment flooded in and years of “dolore intenso” (deep pain) commenced. These were years of prohibitions and strict rules. Francesco, 40 years old and more used to the battlefield than the interior world of a child-bride, commanded in a military fashion and Petronilla’s passion for art and literature was suffocated.

At 19 years of age Petronillafinds herself with three sons, Angelo, Domenico and Emilio and choked by a brutal secret that is kept hidden by a cloak of hypocrisy “fasto apparente” at Castel Sant’ Angelo, and the painful loss of that which she had held dear in her heart, her writing. Enclosed in a narrow room, where even having the sky within reach was of no consolation, months of blurred imprisonment passed. Petronilla later wrote, with admirable irony, of the windows nailed closed to cover the sun, and that not only was she not allowed to write, but the pen and inkpot were hidden away from her. At times it was only her singing that managed to provide some comfort during those long days of solitude.

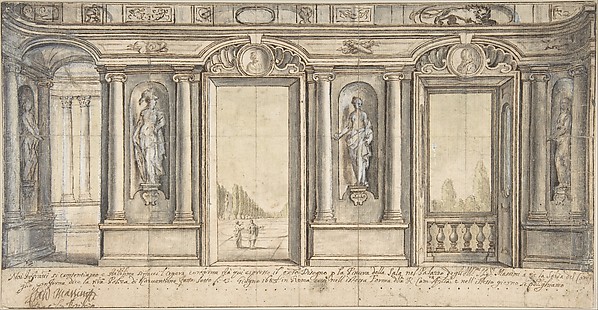

Decoration per Palazzo Massimo all’Aracoeli

We don’t know what made Francesco act so brutally, perhaps it was the fear of finding himself confronted by someone special, someone outside of the usual canons of the time. But Petronilla wasn’t born to be a ‘normal’ woman, tied to the stereotype of obedient wife and obliging mother. She was aware of her own strength and ability to meet challenges, and of her need to display her real talents, inherited from her father, so she managed to do what many other women were too embarrassed to even dream of, she escaped from her “chiuso orrore” (horrific enclosure) in the palace, abandoning her husband and sons – she already had fears of seeing a resemblance of their father in her boys. She seeks refuge in her childhood convent where she also finds her mother. It’s 1690, Petronilla is 26, let’s imagine her arriving at the doors of the convent, desperate, begging to be let in, fully aware of what she has left behind, not only the disapproval of many, but an even worse pain, the estrangement from her sons.

Here in the convent she experiences the poverty resulting from economic dependence on her husband, who will not give her back any part of the dowry. She also learns of the death of her teenage son Domenico in 1694, without having the possibility of holding him in her arms for one last time. This thought gave her much anguish “«ho fatto qualcosa che ripugna anche agli animali» (I’ve done something that is repulsive even for animals) «l’abominio peggiore»(the worst abomination), she tells us, but in turn there is the betrayal that she too has suffered and the loss of her passion, her writing.

Within the shelter of the cloisters she starts to study foreign languages, French and Spanish, as well as Latin, andphilosophy, and she begins to write again, a new birth. Petronilla finally understands that this is her only redemption, her weapon against perverse fate. «Io scrivo, scrivo sul serio. Imprimo me stessa sulla carta. Scrivo per liberarmi, per essere. E per scrivere sono disposta a tutto»(I write, in all seriousness I write, impressing myself on the paper. I write to free myself, to be. And to write I am willing to do anything). But this is still not enough for Petronilla, she requires something else from the world, to be recognised as an economically independent person. To this end she tries to sue her husband for divorce in the Sacra Rota (a tribunal of the Vatican) for «separazione di letto»(no conjugal relations), in an attempt to retrieve her dowry. It was a long fight which ended in her being the victim of the macho justice system which reproached her for her flight and abandonment of her children. The only right awarded in her favour was the right to stay and live in the convent. However her pride is victorious, and in her second Canzone (song) she says «Il mio martir disfido; / l’affronto e il vinco»(my husband defied/The affront is the winner). In addition, in the meantime there have been other successes to console her.

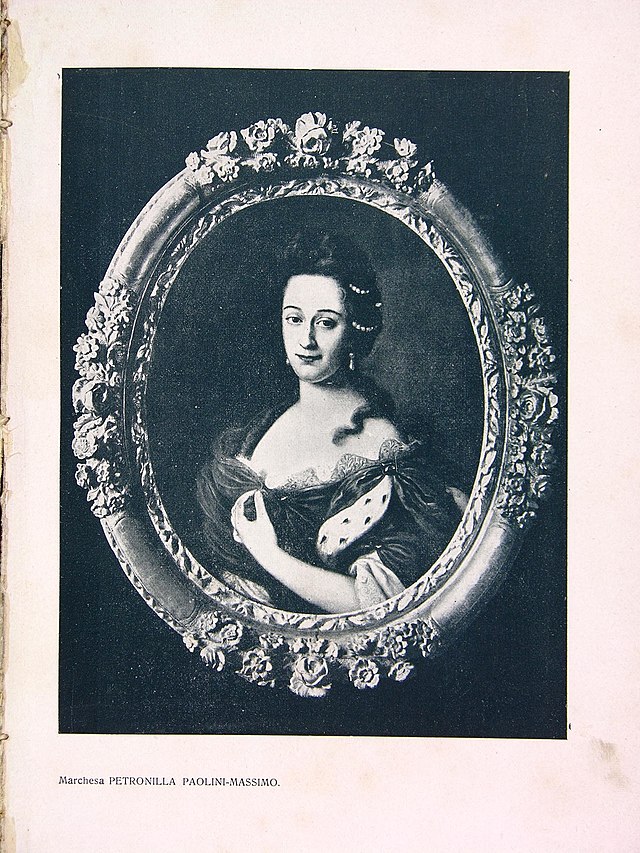

Petronilla Paolini Massimo

In 1698 Petronilla is admitted into the Academy of Arcadia (a literary academy founded in Rome in 1690), joining the other great poets of the era, under the pen name of Fidalma Partenide.“Fidelma”, meaning the transparency of her faithful soul that despite everything never falls into despair, and “Partenide”, for the integral purity of her spirit that maintains her during battle. This is her redemption, her passport into a community that speaks her language and respectfully listens to her thoughts. Crescimbeni and Muratori (two noteworthy poets of the time) praised her. She initiated a serial correspondence with the poet and librettist Metastasio, and is approached by Ovidio, her fellow Abruzzese, for her ability to improvise verse. She was also invited to join other Academies (gli Infecondi di Roma, gli Intronati di Siena, gli Invigoriti di Foligno, gli Oscuri della Pergola, e gli Insensati di Perugia) in recognition of her works.

Even in these academic environs Petronilla doesn’t go with the flow. She mocks the Arcadians for their coy and frivolous forest frescoes inhabited by educated, melancholic shepherds. Her verses are full of a thrilling truth, inspired by her actual life, the drama that she has lived, and so she becomes «un’arcade irregolare nel tessuto delle accademie»(a flaw in the fabric of the academy) as defined by Michela Volante. Her use of autobiography, unusual for the time, includes key social protest and an avant-garde feminist sensitivity. And that’s not all, there is also the classic ideal of poetry as an instrument to overcome time, to remain eternal, to tell a story that not only mocks fate but displays Petronilla’s stubbornness and obstinacy to not give in to it, because as she well knows «non va per via fiorita anima grande, /ma fia che molti e vari mostri affronti»(A great soul doesn’t take a flowered path, but will face many monsters). And in the end fate tires of her jokes and concedes a small gift.

Petronilla’s husband dies in Ferrara in 1707, where he was stationed, with his two sons, to lead the troops defending the borders of the papal state. At death’s door he finally writes to his wife and begs her forgiveness for the suffering he caused her. She sent him her pardon but the letter was never opened. Now Petronilla can finally leave the monastery and take her elderly mother with her to live in the Massimi palace at Ara Coeli, to repossess her heritage and freedom and to finally, after a wait of ten years, put her arms around her sons. It’s the start of her fourth life, a fresh and positive phase, in which she visits the literary rooms of the capital and opens her palace for gatherings of the poets of the academy.She still feels a nostalgia for the calmness of the cloisters, which leans her towards a sober lifestyle dedicated to study, writing and prayer.

In 1709 she makes a trip to Marsica, like a salmon going back upstream, in search of the place of her childhood. She visits Sulmona, Tagliacozzo and Magliano, places which inspire her verse. Then in 1715 her mother dies, the only true affection in her life, causing months of despair accompanied by a remorse for her lost youth, love unexpressed and the freezing of her soul «l’avidità di palma»that replaced her feelings. This loss of her sensibilities and her disappointment as a child-bride formed the basis of an argument in the Arcadia, with another woman of the Academy, Anna Maratti Zappi. Our Petronilla has long held the view that love does not perfect the human soul. After many hours of debate they come to the joint decision that only one type of love, an intellectual one and not a sensual one, can improve the soul.

Petronilla’s numerous verses, written from when she was 18, remained mostly unpublished, some appeared in miscellaneous publications fashionable at the time, others were lost due to neglect by her heirs. We do have five of her sermons and two operas entitled The Illustrious Woman and Temira. This is all we have of the life of the little Marchioness of Marsica, the child-bride, victim of devious conspiracy, the wife that abandoned her conjugal home, the “Poetess of Rome”. But she had other ‘lives’, one example springs from the painting by one of her friends of the Academy, Pietro Antonio Corsignani, which is moving and full of life. In more recent times she has been rediscovered, firstly by Benedetto Croce, who in 1948 dedicated a monographic essay to her, and more recently within the realms of gender studies and women’s history, she has been recognised for her belief in giving women a place within a society organised to give priority to the rights of men.Then there is the life of Petronilla that we still don’t know about because most of her correspondence and writings were lost, or perhaps, for reasons of modesty, she decided to keep hidden.

Walking the streets of Rome, one can stop at the place where Petronilla decided to be buried, in the temple of St Egidio, in Trastevere. She was sixty-two when she died of a chest infection «infiammazione di petto», on 3rd March 1726. Even in this, her last choice, she demonstrates her personality by refusing the pompous ritual usually associated with her status and going for simplicity and internal peace, as she had throughout her life, choosing a barefoot, monastic service, with a habit and wimple from the Teresian religion. Her sons, Angelo and Emilio commissioned the family friend and admirer of the poetess to write her epitaph for the plaque that can still be read to this day. Whilst skimming the words of Corsignani I thought about Petronilla as one of those women who chooses to isolate themselves, who come to terms with their loneliness, who disarm themselves of a social life, keeping only their writing as a weapon, and regain self-possession, like Emily Bronte, Virginia Wolf, Emily Dickenson, or Sylvia Plath. Looking at the tomb and Corsignani’s beautiful depiction, we see what has survived for three centuries, her love of poetry, of intelligence and of life.

________________________________________________________________________________

(*) translated by Gail K.

“I fell in love with Italy in my early 20s, in the early 1980s, when I lived in Abruzzo, in Chieti, for four years. My passions are numerous and include food, film, fun and football. I also love wine, reading, travelling, music, nature, skiing, swimming, horseriding, etc. My academic background is Sociology (BA), Early Childhood (MA) and TEFL. I am now a semi-retired English Teacher, living in Italy with 6 cats; my two sons, in their 20s having flown the nest.”